Special guest and memory enthusiast Anthony Metivier takes us on a whirlwind journey through the magical world of memory palaces and mnemonic systems.

Episode Transcript

This episode transcript has been AI generated for your convenience and accessibility.

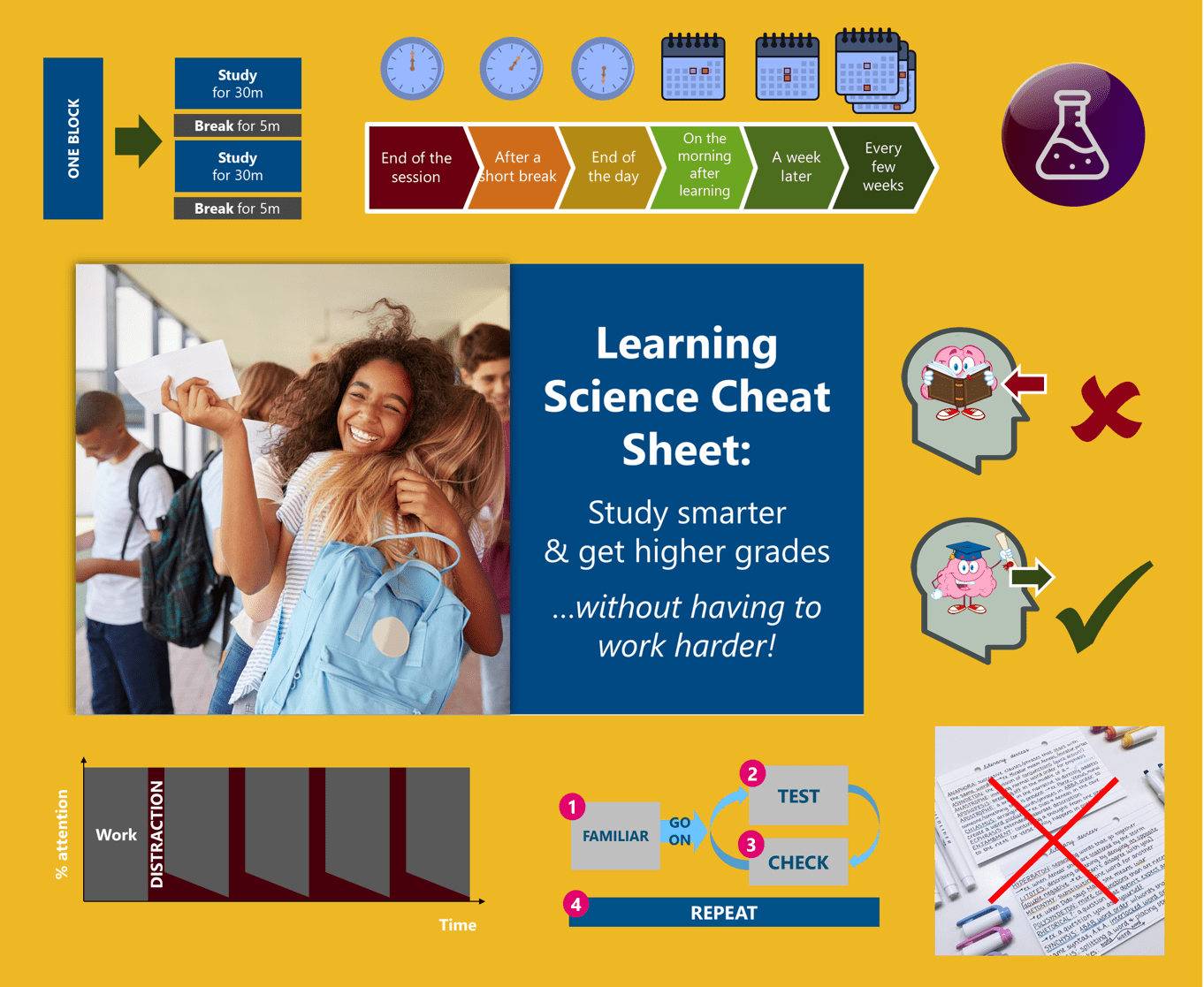

William Wadsworth: Hello and welcome to the Exam Study Expert podcast. Today we’re wrapping up a major series on memory and learning, which we’ve been exploring here on the show in recent weeks, where we’ve been looking at all the ways we can find to help make things stick in memory in the most time efficient way so you can learn faster, remember more, study smarter, not harder, and ace those exams. Most of the series has been very grounded in the psychology of learning and memory and what science tells us about the best ways to learn. It’s very important to me as a psychologist and scientist myself that the advice that we give here on the show is based wherever possible on the available research and scientific consensus. But I also believe there are areas where science doesn’t have all the answers. Take, for example, our work that we share on time management and productivity and how to get more done in the day. Though we may brush on some of the relevant ideas from the psychology of focus or concentration. For example, many of the practical strategies that really help transform someone’s productivity in the course of a day perhaps run a little different ahead of what’s been rigorously studied in laboratory contexts.

Today’s topic is mnemonic strategies, and this is another example of this topic that, well, I mean, it has been studied by science. See for example, episode eleven with Doctor Adam Putnam, who is one of the relatively small community of academics who has taken a research interest in mnemonic strategies. But the community of mnemonicists have honed their craft, but through stretching the limits of what we thought memory was capable of, particularly in competing in memory championships, where competitors vie to perform incredible feats of memory, like remembering strings of digits, hundreds or even thousands. Long as students, if we can find mnemonic strategies that click for us, it can unlock serious boosts to our ability to learn and remember information. So to help us in that goal, I’m delighted to welcome today’s guide to the marvellous and at times almost magical world of mnemonic m memory techniques. The best selling author and formidable memory enthusiast, Anthony Metivier. One of the nice things about Anthony is that he’s not just a, serious authority on this stuff. He, unlike many other sort of mnemonic strategy, sort of memory championship type folk, he takes a really kind of practical and grounded approach to mnemonic strategies as he’s going to talk about in this episode. That takes these strategies out of that context of, you know, trying to memorise 2000 digits, across an hour for a memory championship and kind of makes it all work and apply in the real world to watch more real world practical challenges that we might face in our academic learning. And there’ll be lots of examples in the course of this episode about different ways you can use different mnemonic ideas to help you learn different kinds of information that you are likely to meet in your studies for various kinds of exams. So let’s meet Anthony and dive into today’s episode. Anthony, a very warm welcome to the show. Thank you so much for being here. Let’s start with the definition. What do we mean by a mnemonic?

Anthony Metivier: Well, ideally what we mean is what works. So mnemonic. I think of mnemonics as an umbrella term that means memory technique. So if you are keeping index cards, then that’s a mnemonic technique. If you are writing out the same thing over and over and over again for rote repetition purposes, well, that’s a mnemonic strategy. It’s just a question of like, how good is the strategy, how robust is it, how much does it really help you? So I’m not personally beholden to any particular strategy, but for the purposes of the people who want to learn how to use their memory better, then I want them to know about as many things as possible and then do their own science. Because one of the oddities in memory science is that a lot of the researchers will say, well, we haven’t ourselves use these techniques because that would ruin our objectivity and we would become biassed towards, our subjective experience. So we don’t actually use mnemonics. And I think that that’s right to a certain extent. But it’s also very sad. It’s actually tremendously sad because to use memory techniques really well, you need to be a scientist, you need to treat it scientifically. So you, you say, here are the memory techniques that are available to me now. I’m going to run the experiment with them and I’m going to pay attention to the outcome and then I’m going to see what that outcome says to me and then I’m going to go back into the laboratory and run another experiment. So I think it’s, that’s the core of my training, is that there’s all kinds of ways to get stuff into your memory. Some are more robust than others, but let’s get you doing something, anything, in order to get the data for yourself, because it is an n equals one study at the end of the day.

William Wadsworth: And just before we dive into, perhaps talking about some of the strategies that you feel are, most useful, most robust, I think you’ve also had quite a bit of experience in, sort of applying memory strategies to the world of. In a memory competition, memory world championships, etcetera.

Anthony Metivier: Yes.

William Wadsworth: Do you see, as there kind of being different strategies that are relevant in those different domains, or is it sort of similar strategies applied slightly differently? What’s your kind of perspective on that?

Anthony Metivier: There’s quite a few differences, and it kind of comes back to that principle that we just talked about, which is n equals one. So you will find some mnemonists or memory competitors who just simply don’t do things the same way that other people do them. The core of it is association. So you will take eleven, and you will associate eleven to maybe the Warner brothers toad, as I do. And there’s a reason behind that, which we can talk about why that the Warner brothers Toad would be eleven. But they may or may not actually need to use the Warner brothers toad. They might just be able to imagine the abstract, categorical notion of toadness. Myself, I can’t do that. I need it to be a specific toad. So that’s one layer of difference. Just in the. In the memory world, not all the competitors use the techniques in the same way. But what the core difference is, is that they don’t need to remember that stuff. So, to give you a classic example, Jonas von Essen, he won the world memory championships, and then he went and he was giving an interview on television, and the host said, hey, what’s my name? And he couldn’t remember the guy’s name, right? So not only is he, like, maybe he did use memory techniques to remember that guy’s name, but he didn’t remember the guy’s name. And he. If you asked him and you asked anybody, like, hey, what was the 32nd card in the second division of five minute cards? Right? They’re probably not going to remember ten minutes after reciting it what those cards are, because they haven’t done something to usher the information into long term memory.

And so here’s the core difference. It’s how do you get it into long term memory? But how do you also use the mnemonics in the first place so that it helps you get it into long term memory, easier memory competitors do not have to think about either of those things. They just have to think about when am I going to be tested on what I just memorised in order to make the fewest amount of mistakes. They’re not even worried about perfect. They’re worried about the fewest amount of mistakes on the day of the competition because everybody makes mistakes. I don’t think I’ve Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a competitor winning with zero mistakes. The person who wins, as far as I understand they’ve made the least amount of mistakes on that day. So there’s a. There’s a little bit of a luck factor that’s helping them. But gas them 2 hours later, five days later. Unless it’s a long term competition, they won’t know because they haven’t set up the game to have that duration and they haven’t done what I call recall rehearsal, which is sometimes called spaced repetition. And why would they? Because it’s just 11, 23, 40. five. Ace of clubs, queen of hearts, two of spades, you know, five of diamonds. Like all that sort of stuff. Why would you need to although Queen of Hearts and two of spades and five of diamonds and eight of clubs. That actually is a mem order, that I have memorised for some of the card magic that I do. But I approach it very differently than I would memorising cars in competition.

William Wadsworth: I think there’s something really important that you just touched on there, that idea of kind of recall rehearsal. Because I think there’s some people I’ll talk to about memory strategies and mnemonics and I think there’s sometimes an assumption, not from everybody, but from some people I talk to about this, that this is kind of going to be almost like a magic trick and like a magic bullet. And you kind of apply this strategy and then that just sort of instantly, magically puts it in your memory and then you’re done. But I think what you’re saying there is. Well no, that’s kind of the first step. But we also need to rehearse the recollection. Like it’s Maybe a way to think. I don’t know if you’d agree with this, but maybe a way to think about it is like the mnemonic is like a stepping stone in the river. It helps you across the river, but you still need to practise the jumping over the river. If you never practise that then you won’t be able to recall it to the standard you ultimately want to in the test or examine.

Anthony Metivier: I think that’s a nice analogy. And I think there’s a, potential for many, many, many analogies. And at the end of the day, whatever it is, it is you being involved in how your own mind works. So it comes back to that, like, be the scientist in the laboratory of your own mind principle. Because I know a lot of the metaphors that I use or analogies that I use, they’re always going to hit a large amount of people cold. They’re like a stepping stone in a river. Well, I’ve never stepped on a stone. What are you talking about? Right. and we know that analogy has a problem in teaching because, you know, if analogy worked, everybody would be Zen. It just, it would have caught like wildfire through the entire species. But you’re right. I totally agree with that analogy. The thing is, is I would just encourage people to not to try to process it through actually doing it, as opposed to thinking that it’s this way or that way. Because what we’re doing is actually beyond name and form. The best memory scientists, they don’t know what memory is in the same way that the best neuroscientists, they don’t know where the eye is, where the ego is, where the identity is in the brain. It’s just, it’s just not solved. Some researchers have said they want to get rid of the word memory because it’s not sufficient to the cause of explaining what’s going on.

William Wadsworth: We’ve got about as far as memories are n grammes, which have permanent physical chemical changes at the synaptic junctions, in particular, little circuits that code for certain ideas, by, gosh, it’s taken a long time to get to that, and we’re still pretty shady on, like, the implications of that and what it means and, like, how that forms.

Anthony Metivier: And, you know, I think Aristotle said that.

William Wadsworth: Actually, Aristotle is talking about engrams, really.

Anthony Metivier: I think he’s quite close to that description, actually. If you read Aristotle on memory and how he describes the memory as an aviary with birds that are distributed throughout and they need tending and care, he seems to have intuited that the brain splits information up and puts it in different places, and to care for each of those bases independently is going to make your recall much more robust. Not only that, but he also talks about what is essentially revision and how to do it with what we now, or what. I shouldn’t say we, as if everybody does this, but people who are strange, like me, who love the memory tradition, call ars combinatoria. So ars combinatoria is its own practise. And when it’s done in combination with recall, rehearsal makes everything so much more powerful. But, yeah, I’m slightly joking when I say that Aristotle wrote this, but I would be very surprised if you don’t go and read that and you go, oh, I know why Anthony thinks that.

William Wadsworth: Well, there we go. Wisdom of the Ancients. I’d love to dive in. So, to some of your favourite practical ideas. So, for someone, and I probably would be a fair example of this, for someone that’s relatively new to using mnemonic strategies as you teach them. I’ve got an exam coming up. You know, maybe I’ve got a sort of medical exam to take a couple of months away. What would be some of the first things that you’d want to, teach me to make learning all that information a bit easier?

Anthony Metivier: There’s no first perfect step, so keep in mind, these are tools and toolboxes. These are ingredients in a larger cake. And, you know, I didn’t learn them overnight, and nobody, nobody has to, although I did kind of learn them overnight. It’s just the things that I still had yet to learn accumulated over a long time. So. And this is. This is a thing that’s very puzzling to me about memory, is that I have seen people before my very eyes who have never heard of memory techniques, just perform amazing things on the same day. And I’ve also seen people take years. So the things that I would recommend people understand as quickly as possible is, first of all, that there is no why that it works. So if you’re a person who needs to know why something works, just get past that. What it is is something more. We can focus on how to do it and what it is that I would recommend is a combination of basically five systems. The first system is the memory palace system. The second is the Alphabet system. The third is the number system. The fourth is the symbol system. And then the fifth is the recall rehearsal system. And each of those can mean many more things, and I’m happy to talk about Them. But at the end of the day, why you need these things to work in combination is so that when you look at a piece of information, you have a reference point, a place in space to place an association, and that association is going to be as closely linked to the target information as possible.

So, just to take an example, omnium expedendorum prima este pencia incua per spectiboni forma consistent. That’s hugh of St. Victor who said, choose wisdom first. This is the latin, choose wisdom. First, because in the choice of wisdom is goodness itself. Now, the memory palace, for that is a place that reminds me of the letter o because that phrase starts with omnium. Right now, the Alphabet system is already in the memory palace system. But then the other thing is I have, for the first image, Optimus prime. And the reason why I have Optimus prime is because, like, omnium is not. I probably could have come up with something a little bit more close to omnium then Optimus. But notice that later in that sentence is prima. so Optimus prime and Prima. So it works out nice. But at the end of the day, that’s the Alphabet system. Now, let’s say that there was a number in there like omnium eleven, you know, then I’d have my Warner Bros. Toad. And that would be based on the number system. Let’s say there was an asterisk in there. Then I would have, maybe, I don’t know. One of my favourite constellations is Orion. So I would have, you know, a reference to Orion in there to help remember. There’s a constellation and then the rest is, the recall rehearsal.

And what recall rehearsal basically means is that if you have a memory palace and it has ten words, let’s say, or ten pieces of information, you want to give what Ebbinghaus called primacy effect and recency effect to each and every part of that memory palace in equal doses. Because if you were to just favour the beginning and the end, you’re going to wind up having a severe forgetting of the middle of your memory palace journey. So omnium expedendorum prima estpincia. It’s like I want to go through that sentence forward, but I also want to recite it backwards. And I want to recite the first word, the third word, the fifth word, the 7th word. And then I want to go backwards through the even words. And I know that sounds crazy, but I did that with my TEDx talk. I’ve done it with long form sanskrit mantras that I’ve memorised. I’ve done it with everything I needed to learn in German because I noticed that if I take a list and I follow those patterns using the memory palace station by station by station, or the method of loci, station by station by station, and I make sure that I give equal doses of primacy and recency to each one, then the recall happens so much more faster or, so much more quickly and with greater integrity to itself. And the other part of it. Actually, there is a 6th system. And the 6th system is embrace the mistakes. They are your best teacher. They will teach you so much. If you would just get your ego out of it and go, wow, I’m curious about this mistake. I mean, I had Optimus prime in there and I had Wolverine for Expedendorum, because he’s an X Men and he’s at the pet barn and he’s, like, smashing the door with his claws because it’s a door and it’s the door from the shining and, you know, red rum on the door there. So, like, why did I make a mistake with expidentorum? It should be so easy with all these images. Get really curious about that. And when you ask questions about things, this is the thing that Giordano Bruno talked about long ago in de ombre siderum, which means on the shadows of the ideas. He said, you’ve got to ask questions when you’re memorising, because it is itself a mnemonic strategy and it will help you revisit things. I don’t think he says it’ll help you revisit things with your ego in cheque, but I think he means it’ll help you revisit things with your ego in cheque so you can learn from your mistakes.

William Wadsworth: I think that’s a fantastic point. Yeah. So many students I talked to, we’re kind of afraid to make the mistake. we spend so much of our time at school and university trying to get all the answers right. You know, when we’re learning, you know, we’re not supposed to get the answers right. Part of the process is making those mistakes and learning from them and keeping your ego in cheque. I think that’s a fantastic point.

Anthony Metivier: Yeah.

William Wadsworth: I just wanted to dig in a little bit more to the. To the start of the first thing you mentioned. So, for anyone that’s kind of new to the idea of memory palace, and we’ve pretty much never talked about it on the podcast, which for some people will be really surprising. So, Anthony, you have the great honour of introducing us to this idea, memory Palace 101. Like, how do we go about setting that up?

Anthony Metivier: Right, right, yeah. I just jump in there as if it’s universally known, but it feels like it’s universally known because it’s in Sherlock and it’s.

William Wadsworth: Well, right.

William Wadsworth: I mean, I get people coming to me and saying, oh, you know, I’ve watched Sherlock. How do I have my amazing memory palace for, like, every single thing I’ve ever seen or heard?

Anthony Metivier: I must go to my mind palace, smoke a pipe.

William Wadsworth: Very important.

Anthony Metivier: So the memory palace is a very, very old technique. And we have reason to believe that it’s prehistoric. Probably the idea that you would use a location as a reference point in order to think back to what it was you wanted to remember. So the classic story that they give is simonides of kos and simonides of cost was giving a speech at a banquet hall. And I’ll try to just keep to the short version. Basically, he had an argument with the guy that was arranging the, the talk that Simonides gave. And he said, you thanked Castor and Pollux in this talk. So if you want me to pay you the entire fee for your talk, why don’t you ask them to pay half of it? Because, you know, you didn’t even thank me in the, in the talk because they’re fighting over the bill or whatever. So at this moment, a messenger comes into the banquet hall and says, simonides, you’re wanted outside. And outside, lo and behold, are caster and Pollux. And they’re like, a little bit closer, please. And then when Simonides is a, respectable distance from the banquet hall, a earthquake happens, destroys everybody inside. And Simonides just happens to have memorised the names of all the people that were at the banquet hall. And he remembered where they were sitting. So he helped the authorities identify the bodies so that people could appropriately respect their loved ones.

And that is the idea of the memory palace or the method of loci, where a piece of information is such as the name of someone seated at a banquet is going to be easier to recall because you’ve given it a location. Now, theoretically, if simonides of cause, actually used memory techniques, he would have used their body or their location for his image. So, like when I talk about images of Optimus prime for omnium and X Men for expedendorum, theoretically, he probably would have had that image, like on the person’s shoulder or over their heads. So that’s how he’s remembering that it’s John at that table, or William sat over there sort of thing. It’s a location based mnemonic. The image, the association that gives you the target information, is at the exact spot that you can revisit in your mind. Now, notice this. A banquet table is structured. It’s got the head of the table, and then you can go in a square around it. I don’t know. I wasn’t there, so I don’t know. Maybe it was a different kind of banquet table. But, you know, if we just use logic, would he would have had a journey to follow? Which is why this is sometimes called the journey method. And you would just go from John to William to Bill to George to Edmund. You know, all that. Those are not ancient greek names, but Xenophon, Xerxes, Xanthippia, these kind of people, all exes, of course. And, he would have. He would have just named them in the order that he remembered where they were probably by following this journey.

And we have hand memory palaces that are very much like that. I talked to Tyson Yonkoporta one time, who is someone who calls the people like myself and yourself, who protect, study techniques and protect memory techniques, the custodians of memory. And he teaches in one of his books called Santok, the Hand Memory palace, where in a meeting, you remember to connect, respect, reflect and direct. And for listeners, I’m pressing my thumb to my forefinger for connect and my thumb to my middle finger for respect and then my thumb to my ring finger for reflect and then my thumb to the pinky finger for direct. And that just. I’ve never forgotten that. And it’s just using my hand as a memory palace. Same thing for, what do you call them? This is one of those things where I have to actually search for what you call them, the carpal tunnel bones. Right? You’ve got the navicular, which is sometimes called the scapoid, which is next to the lunate, which is next to the triangular, which is the next to the pisiform and the hamate. And then you have, oh, what is it now? I’ve lost it. Oh, the capitate. And then you have the trapezoid and the trapezium, I think. Anyway, I’m not a meta medical person, but I was helping a student remember that one time, and I just used my wrist to help me encode all those things. But what I really have is someone navigating for the navicular. He’s navigating to what? To a scat. A scaffold to help me remember. It’s the scaffold. And then the lunate is next to that Abba sings about, you know, What do they sing about? Why do I have Abba there? Waterloo, that’s why. Lunate loo, that sort of thing. Anyway. And then you get decapitated. We have Captain Crunch. Ah. And so on. Pisa form is Prince roller skating on pizza. Like, these images are actually not in a memory palace. They’re on my wrist. And, you know, you can do it for anything. The extensor pollicis brevis. It’s, if I remember correctly, that’s what it’s called. That’s up here. And I just remember this stuff using my own body as the memory pulse. So the point is location based mnemonic. I’ve placed the association in the location. That helps me think back to it and remember it. Yes, you can do recall rehearsal on your wrist. You just go from the navicular, also called the scapoid, and then you skip the lunate, and you go to the triangular and so on. So it works everywhere. And the entire universe is a memory pulse.

William Wadsworth: So in that bones, the wrist example you gave. So you’re coming up with that, slightly zany, funky, visual, memorable visual imagery for each one of those ideas, kind of linking those together in your mind as some kind of story, this sailor navigating by the light of the moon or whatever it was. And then, you know, each one of those steps, you’re kind of putting it, you know, in the case, the bones of the wrist, you know, your memory palace is. The location’s on the wrist itself, which seems to be quite a good idea. Otherwise, you know, I’ve heard people often say, you know, using the rooms of your house or different locations, go on a journey around the house. Is that sort of what you teach as well as kind of your default vanilla version of your memory palace?

Anthony Metivier: I do, but I tried to teach it in a particular way. Okay, well, because what a lot of people do is they see a TEDx talk or something like this, and they see a guy say, yeah, so start at your door and then move in to the building. And I always think, why? that’s just leading yourself into a dead end. Why wouldn’t you find the dead end and start there? So you can lead yourself out of the building and always have m more stations to add or loci, which are the individual spots that you’re going to strategically use to assign information. So you want it to be ever expanding insofar as that’s realistic. Obviously, you want to avoid, making them so large that you can’t do recall rehearsal effectively. Because the whole point of it is to optimise for revision or review or as I call it, recall rehearsal. And the reason why I call it recall rehearsal, by the way, is because I don’t think of memory as a movie. I think of it as a theatre play. So you really want those. Like, when I have Captain Crunch for capitate, like, I want him to do the theatre shtick. And it doesn’t have to be the same way at, the last time. It just needs to do the job of getting the information back as opposed to perfectionism or all this sort of stuff. Like, I really don’t try to make it the same way all the time. And again, it’s that mistake thing. If you can run with your own mistakes, you’re going to be a lot better and actors can do that. So I, I’ve really thought a lot about this rehearsal thing and theatre of memory as opposed to like movie of memory or something. Because a lot of people, they just want perfect. They talk about photographic memory and to me that just seems like the most unlikely thing to achieve. And also, I mean, photography, it’s such an old technology, you know, we would want the David Webb Web scope or whatever. Is it David Webb? Who has that?

William Wadsworth: James Webb?

Anthony Metivier: Some people say James Webb and some people say David Webb.

William Wadsworth: Oh, is it? Okay, fine.

Anthony Metivier: We’ll have to look at it. I don’t know. I want to look it up.

William Wadsworth: So if I’m trying to learn for, this upcoming exam, do I just kind of have one memory palace for my entire. Like, if we’re using flashcards, for example. So I know some students have got like 8000 flashcards for an upcoming exam. And each one of those would be like a nugget or a unit of knowledge. Would I put like each one of those 8000 in a separate location? Or do I kind of use the same memory palace over. Do I use like one version of it for one topic and then you use the same layout and kind of put a whole different set of information on for topic two and then, like, do I have separate policies for each topic? Like, how does all that work?

Anthony Metivier: Yeah, yeah, let’s talk about that. But let’s pause on this mistake here because I just looked it up. You’re right. Or at least, my first glance here is James Webb. And this is something that will happen to you. You will record something in your mind and then it will mess up. because I remember speaking with a friend of mine and I think I said, James Webb. And then he said, no, it’s David Webb. And then I went and changed my original thing and then. Anyway, somehow I got screwed up there. The point is these things will happen to you and you’ve got to kind of be like, I am. Call it out. Call a spade a spade. You messed up, right? And then think about it. Get curious. It’s like, well, why did that happen? And I’m just thinking my friend Rob now. And I was like, yeah, we had this conversation and then. But the other thing too is that you don’t always even remember the specifics of the details. So really don’t. Don’t cause problems for yourself, because you will make mistakes that remember the best memory. Competitors, they win because they make the fewest mistakes on the day of the memory competition, not the most. And I make mistakes a lot, but I always get really curious about it and then just want to pause on it and reflect on it and think about it. And the problem with memory, which I think you probably know very well, is that there’s a part of it that’s often very confabulatory. You’re making things up as you go. And when we tell stories about ourselves, we. We actually are changing our memories. And it’s. It’s one of the things that I’m terrified of, because I’m on many, many podcasts over the years, and, you know, we always do the origin story. And then I often wonder, while I’m telling this, oh, I hope that I’m like, you know, not creating some totally different version now, because I’ve actually changed my own memories by changing it. Anyway, this is, To me, this is one of the most fascinating things about memory, is the role of the mistake.

Okay, so, now to your question. Part of the way that I like to operate is to have multiple memory palaces that are rather small and to use numbers to guide me, but not make it a numbers game. I mean, all of my sanskrit stuff that I’ve memorised for my meditation practises is now at least 2000 words. The last time I counted it was 1700 some odd words. If I were to sit there and count all of it out in advance, I would have frustrated myself and gave up. You know, it’s too much. But rather, what I do instead is I think on a very project by project basis and think, okay, so what’s going to be the smallest possible memory palace here? And then just get started knowing that I may need more than the memory palace that I’ve, assigned for this one thing. Or the other way to look at it is to have a memory palace for every letter of the Alphabet and then just rotate between them, which is not the greatest thing to do. So another way to do it is, if you’re studying a textbook, to have a memory palace for each chapter of the textbook. And you don’t have to have your memory palaces arranged alphabetical in the sense that, okay, so this word starts with omnium, or this phrase starts with omnium. So I’ll go to my friend Owen’s place, or whatever you can also have them numerically arranged. Now, if you have a number system, they’re going to be alphabetical anyway. Because when you have number systems, your number systems are based on the idea that, that it’s words. So just to stick with our Warner Toad, if I use a place where I know the address is eleven, well, that is going to be also possible to call that the Toad memory palace. But let’s say it’s chapter eleven. I can think of another place that has an address eleven. Or I can use 11th avenue or 11th street, or I can use Todd and still tether it to a toad, what have you. But the idea is to really zero in and focus on that individual chapter so that we can optimise for the recall rehearsal.

The other thing I should say too, is it’s not always, always 100% memory palace. So what I will do, and, I’ll just show you this visually, since we’re here together. But when it’s really challenging stuff, I will draw often. So what I’m showing you now is a jar. That’s nice with Indiana Jones. I know I’m not a great artist, but that’s supposed to be Indiana Jones, and he’s whipping a briefcase. And my mandarin pronunciation has never been all that great, but it’s jury, which means career, right? And so the jar plus Indiana Jones whipping a suitcase, that gives the notion of career. And the thing is, is I never have the information, or very rarely, I don’t have the. The answer on the back because the answer is in the image, right? So why is, why is there a jar next to Indiana Jones and he’s whipping a briefcase? That that’s the answer. This is part of act of recall, is when you challenge yourself. So there’s that. And often my memory palaces will have a lot of cards, especially when I’m memorising. Like, I study a kind of logic called dialitism, consequences of which are para consistencies. You have to say that in a radio voice. But I, have to have symbols for operator and condition and totality and all that sort of stuff. And I have had to draw out a totem pole next to the symbol of totality to remember that that particular symbol means totality in this particular non classical logic. So it’s still in a memory palace and it still goes through recall rehearsal. But I will supplement this by actually making drawings. The thing I tend not to do is to not have an answer on the back. If I have an answer on the back of the card, I, will use, what do you call it a cloze test. Technology. Do you know that? Or technique. Sorry. So cloze. C L O Z E is the idea that you have partial information. So if you were memorising, I don’t know, something from Shakespeare, if there be nothing new but that which is have been before, how are our brains beguiled? That’s opening of sonnet 59. Instead of writing out the entire line, you would have. If they’re new, you know, that sort of thing. And then you would have to. You’d have a blank line and you would want to fill in that blank space. So that’s what closes. A closed test. Your cloze, I believe it’s spelled. Anyway, I. I do some of those things, especially with super challenging information, because sometimes I just can’t come up with associations. So I will do my best and then still make it a challenge that I have to complete a puzzle because it’ll form the memory a lot faster.

William Wadsworth: Yeah, that’s. No, that’s great advice. That’s great advice. I’m really interested because, like, I can see how to use the system you described with the numbers and, like, you know, you might associate different numbers with different ideas, and that helps you kind of chunk and code sets of numbers that you demonstrated with the, bones of the wrist. Like, you’re forming those kind of visual associations with different bones. I can see how that works. I’ve extensively used a very simple form of mnemonic of just, you know, what are the first letters of the keywords in a set of items or a list, and what do they spell out? And can I recognise patterns in those letters? And I just find that just an incredibly powerful and flexible tool that I use the whole time, but I’ve never. For myself, I’ve, like, I’ve been aware of the method of loci memory palace for a long time, but I’ve never personally found it to be. To be useful to me. So I’m always curious when I hear people like yourself or, you know, sometimes I’ll have kind of conversations day to day with students and they say, oh, you know, I’ve used this and it’s been brilliant. And, you know, that kind of piques my curiosity because I’m sitting here thinking, well, like, I’ve known about this, but it’s never quite, quite clicked for me. Like, are there some people it works, for, other. Some people it doesn’t? Or is it just that I’ve not yet got to the kind of.

William Wadsworth: The level of skill and expertise with.

William Wadsworth: The technique that I can use it well, or like, what do you think might be. Might be going on for me?

Anthony Metivier: Yeah. This is, I think, the human nature question in some sense. I mean, knitting isn’t for me either.

William Wadsworth: Yeah.

Anthony Metivier: I have a friend, he knits like crazy. He just loves knitting, right. But it’s not for me. So, you know, is there something wrong with me or so forth? No, I’m just. I’m just not into knitting, you know, or another friend of mine, he’s so into baseball, right? And he’s into betting on baseball. Like, he just loves that stuff. He can think about Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman and all these people all day long, right? He asked me how would he remember those names. So I told him, and now I can’t forget them. Maybe I got them wrong, like David, Webb when it’s supposed to be James Webb. But anyway, like baseball players, right? I think I got those guys, right. Anyway, the whole thing is, is that I. That to me is a. Is a fascinating mystery. And I don’t know the answer. But at the end of the day, I think we also don’t know why not everybody plays the piano. We don’t know why not everybody’s in debate club. I can’t understand why everybody wouldn’t practise a martial art. Least enough to get to the level that I’ve gotten to, you know? But, like, it’s just the way the world is, you know.

William Wadsworth: I still hold, Like, I still like the idea that this might be a strategy that is good for like, I don’t think I’ve written myself off from. This isn’t. This doesn’t work for me. And I don’t think I’ve closed myself off to that. It’s. Yeah, it feels like maybe I just. Maybe my natural tendency to it, is a little bit weaker than some other people. So it takes a little bit more work and practise to get to the point where it is something that has, you know, good usefulness, me. And clicks.

Anthony Metivier: I think another way to look at it is that everybody does do it. It’s just not necessarily that they are interested in the art of memory itself because it is its own thing. But I think everybody goes, oh, you know, what is that like? Or they. When they try to remember something, they’ll repeat it and they’ll repeat it and they’ll repeat it and they’ll, you know, maybe sing it a little bit or try to rhyme it or whatever. Like, I think. I think it’s quite, quite normal to use memory techniques and to use even mnemonics. But where is the fascination for really nailing this? What is this? And I, think part of the problem is that it has been territorialized in the 20th century in particular, with a tendency that’s carried on into the 21st century to be taught primarily by either charlatans or by people who won’t admit when they make mistakes, which is charlatanism. Or they will, be memory competitors. And memory competitors don’t need long term retention, so they’re not telling the whole story, and they often don’t know it. And then it really helps to know the history, I think. I think that not everybody’s going to fall in love with the history, though, but I think it’s very hard not to fall in love in the history. If you really start to look at guys like Jordano, Bruno, Robert Flood, Aristotle, as I mentioned, Ramon Lowell, like, man, this stuff is way more exciting than what’s on tv. It’s like a Marvel universe unto itself.

William Wadsworth: The memory marvel user. I love that. I love that. That’s fantastic.

William Wadsworth: Well, look for me or for anyone else listening that wants to level, up their skills and their abilities to use these strategies and apply them for ourselves. You’ve given us a wonderful introduction today, and thank you so much for being so generous with your time and your wisdom. What’s the next step on our learning journey? So, if we want to, step further into your world and learn more, where do we go next?

Anthony Metivier: Well, I would suggest finding anything that you think you’ll use. Whether it’s my stuff or somebody else’s stuff, there’s going to be a match for you, I’m sure. And I think anybody can get rolling. So if you want to come to my site, it’s magneticmemorymethod.com, and I do all kinds of wild and wonderful experiments. I’ve got games that I’ve put together. I’ve, created the memory detective novel series. If you’re not into courses and stuff like that. But I’ve also got the courses, and I just try to try to be kind of, like a university level place where you can understand the science of memory and everything that you would like. But my larger message would be, figure this out, you know, one way or the other, and understand that there are those five systems. Lots of people are going to talk about them in different ways. But Giordano Bruno said something that I’ll never forget, which is he said, and I think he was right, anybody who thinks long and hard enough about these techniques will come to the exact same conclusions that I have. And this is very important, and it may be part of the answer, why not? Everybody’s attracted to it. It’s because it’s actually a form of logic, it’s a form of computation, and it does perhaps attract people who are attracted to saying, like, algebraically, or in some form of calculus. This is that. We’re going to substitute this for that, and then we’re going to place it here, and we’re going to just be able to basically make equations. So, because it’s premised on the logic of what information is, and it’s premised on the logic of how space works, Bruno’s right. Anybody can figure this out. You could. You could derive it without any study if you. If you really just thought about it. And I hear from people all the time, they email me, and they’re like, yeah, I was doing this when I was a kid, maybe not exactly like this, but I have sort of figured out something like this myself. And it’s like, yes, it’s. It’s just raw, pure logic, you know, at its core. So if you feel like it’s too hard and all that sort of stuff, well, I’ve got hours and hours and hours of cheerleading, but at the end of the day, you’ve got to start. And, oh, sorry, I say five systems, but I got to add the 6th system, which is embrace your mistakes, because they’ll be your best teacher, and they’ll actually help you inquire into the nature of your own memory and try to track back, where did this go wrong? Where has it gone awry? And then it will be the greatest gift, because you’ll be able to use the techniques themselves to tell a new story, and it’s the story you want to tell, which is, you know, greater accuracy, more confidence, having more fun with your mind. And, I think at the end of the day, at least for me, what’s become very attractive about it is that it helps you just not be bowled over by your own ego to the point that you just, you just feel so alive and happy to just be so. Yeah, that’s where you can find me.

William Wadsworth: Outstanding.

Anthony Metivier: I think if you just put Anthony memory, you’ll find me m. If you can’t remember magnetic memory method.

William Wadsworth: Anthony memory or magnetic memory. Yeah. Anthony, thank you so much, for this conversation. It’s been really fascinating to chat. thank you so much for the time and sharing your wisdom once again.

William Wadsworth: and look forward to talking soon.

Anthony Metivier: Appreciate it. William, thank you very much.

William Wadsworth: Well, thanks again, Anthony. For that fantastic conversation. And if you’re interested in learning more from Anthony, there’s a couple of places you can go. If you head to ExamStudyExpert.com/kit, you can access a free memory improvement kit that Anthony has created, a free resource that helps you get started with some of his favourite mnemonic ideas. And if you’re interested in the big Kahuna, his full blown mnemonic strategies course, you can find that via ExamStudyExpert.com/mmm m for magnetic memory methods. If you go through either of those links and ultimately go on to make a purchase, the first option is a free kit, but later you have the option of upgrading to a bigger course with Anthony if you wish to. If you go through either of those routes and go on to make a purchase, then Exam Study Expert will earn a small referral fee on your purchase, which is a great way to support the show. So thank you in advance if you do go on to, support Anthony’s products and in turn support the exam studio Expert podcast as well.

So want those links? Once more it’s ExamStudyExpert.com/kit K I T if you want the free memory improvement kit or add mmm m m m for magnetic memory method to cheque out his full blown memory masterclass course. It could be a particularly good fit if you have a huge amount to learn for your exams or you’re just really interested in how to use mnemonics as a way to maximise your memory powers. And that is a wrap on the learning and memory series we’ve been covering over the past few weeks. A big thank you to all my guests and my wonderful listeners. I hope you’ve enjoyed this series as much as I have. We’ve put a lot of work into finding really great guests to bring you across this series, so please do take a moment to share your favourite episode with a friend. Or if you’re a teacher, perhaps pass the episode on to a colleague or especially your students and encourage them to have a listen. Sharing the podcast is a small but incredibly powerful way to support the show and to do a good deed for whoever is on the receiving end of the share into the bargain. Thank you so much once again for listening today and I will look forward to seeing you back here again soon. Wishing you every success as always in your studies.

We’re wrapping up our Memory and Learning series here on the Exam Study Expert podcast by diving into the marvellous, and at times a little magical, world of mnemonic memory techniques.

Our guide today is bestselling author and formidable memory enthusiast, Anthony Metivier, who takes us on a fantastic journey full of practical strategies – and a six-step system – capable of transforming how you learn and remember information.

Featuring a wide cast of memory-capturing characters, from Optimus Prime and Wolverine, to Sherlock Holmes and Aristotle, this is the episode for all the budding memory enthusiasts in our audience.

Access a FREE memory improvement kit, created by Anthony and full of his favourite mnemonic ideas at:

>> https://examstudyexpert.com/kit *

Or discover his full-blown mnemonic strategies course, Magnetic Memory Method, at:

>> https://examstudyexpert.com/mmm *

*Disclaimer: Exam Study Expert may earn a referral fee from qualifying purchases of books and courses we recommend, at no extra cost to you. Our guests work hard as creators and authors to make great educational materials to help you – thank you for supporting them, and this podcast!

* * * *

Mentioned in this episode:

Episode 11 of the Exam Study Expert podcast, with Dr Adam Putman: https://examstudyexpert.com/adam/

Anthony’s TedX talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kvtYjdriSpM

To learn more about Anthony:

Visit his website at:

Hosted by William Wadsworth, memory psychologist, independent researcher and study skills coach / trainer. I help ambitious students to study smarter, not harder, so they can ace their exams with less work and less stress.

WANT ME TO SPEAK AT YOUR SCHOOL? Learn more at: https://examstudyexpert.com/revision-workshops

Get a copy of my ultra-concise “6 Pillars Of Exam Success” Cheat Sheet at https://examstudyexpert.com/pillars/

**As an Amazon Associate, we may earn from qualifying purchases, at no extra cost to you. We make these recommendations based on personal experience and because we think they are genuinely helpful and useful, not because of the small commissions received.